When working to improve a process, it is not enough to implement a solution and stop. Without a plan to maintain the gains, at the first sign of trouble, systems will revert to what has been comfortable in the past. That usually means a return to some past operating procedure. To prevent this, there must be a linkage of the improvement to the management system. This involves monitoring important metrics, documenting methods and procedures, and providing a strategy for dealing with problems in the future.

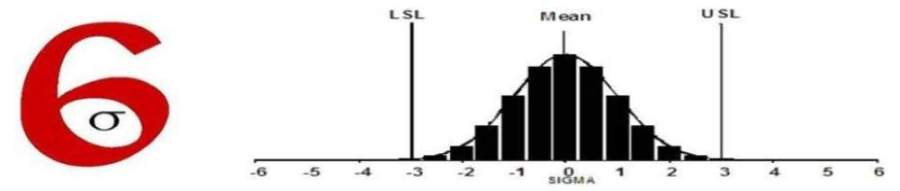

This is the purpose of the Control Phase of a Six Sigma Project. It involves a plan to maintain the gains from the new process, and building that plan into the management system. This will provide for on going accountability. Considering that process improvement projects will typically cross functional boundaries, the various process owners, and what they are accountable for, will be need to be specified, and included in the plan, in order to insure long-term success.

The result is consistent customer satisfaction, a linkage between quality initiatives and strategic objectives, direction for future improvement activities, and a reliance on data by the process owners. These are the ingredients of successful improvement projects

Discipline (Standardization)

Discipline, in this case, applies to the adherence to standardization. Just as a disciplined athlete adheres to a standard practice routine to reach the highest level of their performance, a business must have the discipline to adhere to proven methods of doing work. This is standardization.

Standardization is about making sure that important elements of a process are performed the same way every time, as prescribed by the standardized process. A lack of consistency will cause the process to generate defects and compromise safety. Standardization also provides predictability, which allows the process owners to prevent problems before they affect the customer.

In a process improvement project, the improvement team can use the PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act) cycle to find the best way to do the work. The data collected in the PDCA cycle becomes the basis for changing a process, or for leaving it as is. Eventually, when no further improvement is mandated, a standard work practice is developed.

When a process or practice is standardized, changes are made only when data shows a need to change. This prevents individuals from doing the work the way that seems best to them, thus compromising quality and negatively affecting the customer. The objective is to maintain consistent quality over time in spite of environmental changes.

Documentation is an underlying principle in standardization. Making sure documentation is up to date and utilized encourages the ongoing use of standardized methods. In addition, documentation provides the information necessary to anticipate problems and to see where potential improvements can be made.

If managed properly, standardized work establishes a relationship between people and their work processes. This relationship can enhance ownership and pride in the quality of work performed. From the customer’s perspective, standardized work keeps processes in control so that the highest quality products and services are provided. From the service or product provider’s perspective, standardized work improves safety, improves employee morale, controls production costs, and provides business longevity by returning satisfied customers.

Standardization has three components: elimination of waste, workplace simplification (5-S philosophy), and work process analysis. All three of these components are necessary. If work is standardized without waste elimination, waste production becomes standardized. If work is standardized without workplace simplification, complexity becomes standardized. If a process is not being measured, it is not being managed.

The place to do all of this documentation is in a work process analysis document. This tool documents how work is done. It is convenient to look at work process analysis as a detailed description of the process’ process map. It can also be a documentation of workflow through an area of space (e.g., a factory floor). The restraints of this article prevent me from including a Work Process Analysis template. You can get this, though, by visiting my website at leanmeanprocessimprovement.com.

The work process analysis tool also makes an excellent training tool. The process steps are detailed and the expected cycle time is given. This becomes a target for the process operators. The process diagram can also be the floor layout of the workflow. The exact content is dependent upon the needs of the process owners.