For the most part, all of us have a robust fear of failure. We are good at counting the cost of trying and failing. We are also pretty much aware of what we don’t want to lose. The result is that we miss opportunities due to not taking the risk of possible failure.

Tag Archives: Six Sigma

Cycle Time and Utilization

In order to improve my on-time delivery of service, do I add resources to my process, or do I try to improve my process cycle time? The first consideration is that increasing resources increases your cost of operation. Improving cycle time does not. Another way to look at this is to compare your process cycle time with percent utilization of resources.

There is a relationship between variability in cycle time and percent utilization of resources. The source of this variation can be found in quality, rework, employee issues, etc. When variation is high, the percent utilization of resources reflects that variability and can impact on-time delivery, cost, and knowing how to allocate capacity (hiring, capital equipment, etc.).

An example of how this relationship works is displayed in the graph below. As the percent utilization of your capacity increases, task cycle time also increases. The increase in cycle time is relatively flat at first, but eventually, the curve becomes steep.

The two curves in the graph above represent a 3 sigma level process (high variation) and a 5 sigma level process (low variation). If a customer’s time to delivery requires process cycle time to be less than 4000 seconds, the 3 sigma curve fails to meet that criterion at about 65% of resource utilization. The 5 sigma curve, on the other hand stays capable of meeting the criterion all the way up to 100% of resource utilization.

A business with a high variability in cycle time will have to add capability much sooner (lower utilization). This is not good for bottom line costs. This clearly demonstrates why lowering the standard deviation in cycle time of the process becomes important.

An additional take away from this chart is that as cycle time or utilization increases, so does the probability of failing to meet on-time delivery targets. Again, the lower standard deviation (higher sigma level) process has the lowest probability of failing to meet on-time delivery requirements at any utilization percentage.

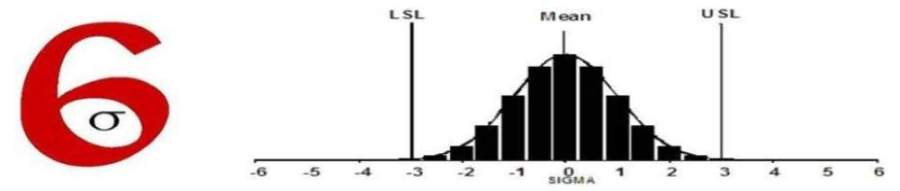

What this means is that is better to focus first on cycle time in order to improve on-time delivery, as opposed to simply adding resources to a bad process. This is where Six Sigma comes in. A six Sigma process improvement team will address the root causes of variation in the process; thereby improving the utilization of existing resources. This is akin to giving your car a tune up to improve its fuel economy.

Finding Sources of Variation

Typically, the most suspect processes or process steps for introducing variation are manual or judgment oriented in nature. For example, if an individual applies personal judgment within a process you would expect to see bias or higher variation in the process output. Automated processes will typically have more consistent performance and lower variation.

One of the best ways to find these manual or judgment steps in a process is through the use of a process map. As a process is mapped, decision points are represented as diamonds. This becomes the first place to look for variation.

When mapping a process, information from both the process owners and the Six Sigma team’s observations are used. There are situations where the process as described by the process owners is really from the “as we think it is” or “as it should be” world. The Six Sigma team that falls into this trap is doomed. In these cases, the process owners may know the standardized process, but chose to not follow it.

On a project I worked a few years back, there was too much variation in the concentration of petcoke being blended with the coal burned in a business’s boilers. The result was either too much petcoke, resulting in a violation of environmental parameters, or too little petcoke which increased the cost of operation.

The fuel feed system was comprised of 2 conveyer belts that fed a third conveyer belt. One of the feeder belts fed coal and the other fed petcoke. The third belt, called the silo belt, fed the boilers. The concentration of petcoke loaded to the boilers was controlled by the belt speed of each of the first two belts.

Additionally, the silo feed belt was designed to start empty and, as a result, was the last belt to be shut off so that it would be empty when stopped. The two feed belts were designed to be started empty or full.

The process of starting up the fuel feed system was to start the silo feed belt first, the coal feed belt second and the petcoke feed belt last. All belts were to be empty when started. The shutdown process required that the petcoke belt be shut down first, after it was empty. The Coal feed belt was to be shut down second, when it was empty. The silo feed belt was to shut down last when it was empty.

The first step in the team’s analysis of the variation issues was to compare each shift’s start-up and shutdown processes. The Six Sigma Team did not take for granted that all shifts were compliant with the standardized start-up and shutdown processes, since the computer systems allowed them to change the order of startup and shut down.

What we found was that one of the four shifts shut down the coal and petcoke belts full, and then shut down the silo feed belt when empty. When starting the system up again, this shift would start the silo feed belt first and then both the coal and petcoke belts simultaneously. This shift had a low variation in petcoke concentration (within variation). Much lower, in fact, than all the shifts put together (between variation).

Another of the shifts would first shut down the petcoke feed belt full, then the coal belt full, then the silo belt when empty. On start-up they would start the silo feed belt first, then coal feed belt, then the petcoke feed. This group had the highest within variation in petcoke concentration, but still lower than the between variation of all the shifts put together.

The other two shifts followed the standardized process of start-up and shutdown. Their within variation in petcoke concentration was higher than the first shift, but lower than the second shift.

What the team had found, so far, was that two of the four shifts did not follow the standardized process of operation. Even so, the variation within each shift was within tolerance. The team then matched up emissions logs with the petcoke feed logs over a three week period. What they found was that the interaction of the different shifts created significant swings in petcoke concentration. This “between” variation turned out to be the root cause of the variation problem.

The solution was to get all sifts to follow the same process. A team meeting with representatives of each shift resulted in an agreement to follow the first shift’s start-up and shutdown processes. This became the standardized process for the plant’s fuel feed.

The Six Sigma team monitored the fuel feed process for four weeks after the agreement to measure the results. They found all shifts in compliance with the standardized process and a very low variation in petcoke concentration. The low variation allowed the plant Operations group to incrementally increase the petcoke concentration and thereby reduce the plant’s operating cost.

One conclusion that the Six Sigma team made was that compliance with standardized processes is higher when the process owners were part of the dialog that creates the standardization. Processes are processes, but people are people. Processes are developed to serve the process owners (people) not the other way around.

Another conclusion was that communication between groups needed to be improved. The different groups need to understand why standardization is necessary and they need to know how to recover from unforeseen process upsets. In this case, what is the standardized process for start-up and shutdown when system maintenance required a different shutdown condition than normal? This latter situation required an expansion of the process management plan to include all pre start-up and per shutdown scenarios.

Lean and Mean Process Improvement CD and Audio Book

Lean and Mean Process Improvement is now available on CD as a PDF along with an assortment of Six Sigma Tools. Email me at walt.m@att.net for details on how to purchase this CD.

Work started last week on converting Lean and Mean Process Improvement to an audio book. This work is in progress. I will post notification about availability as soon as it is ready. If you email me at walt.m@att.net, I will notify you when it is ready for distribution.

Practical Application of Hypothesis Testing

By following a consistent format the Six Sigma team and its customers can better understand and explain hypothesis test results and conclusions. Reviewers know exactly where to look for information, which will increase their confidence in the results. This is an example format to use.

Practical Problem

This is a statement that describes the practical question to be answered by the test. It is written in process owner or customer language and states what is being asked. It is phrased as a question.

Statistical Problem

This is a statement that describes the specific hypothesis test that will be used along with a definition of the “null” and “alternate” hypotheses for the test. The statement is written in the specific statistical terms required by the hypothesis test being used.

Statistical Solution

This is a statement that describes the solution to the statistical problem. It too is written in the specific statistical terms required by the hypothesis test used.

Practical Definition of the Statistical Solution

This is a statement that describes the statistical solution in practical terms. It is written as a statement and answers the practical problem question in step one. Process owner or customer language is used. No elaboration is allowed. Just the specific answer to the specific question posed in step one.

Example:

Practical Problem:

The vender promised service in an average of 5 minutes. Is this a true statement?

Statistical Problem:

Single population t-Test with H0: m = 5.

Ha: Service time does not average 5 minutes. Confidence interval equals 95%

Statistical Solution:

P = 0.0000, H0 is rejected because P < 0.05.

Practical Definition of Statistical Solution:

The service time does not average five minutes.

Hypothesis testing does not establish the why or how. Other process knowledge will help answer these questions. Note that the way the test is set up, it does not indicate whether the actual average service time is greater than or less than 5 minutes. The test can be restructured to look at one side of the data’s distribution, or other process information can be used to determine the direction from 5 minutes the distribution’s actual mean really is.

Intuition and Data Analysis

The analysis of data is now, and always has been, problematic. We are not machines. Our thinking is affected by intuition and experience, which are not empirical in nature. In business, Six Sigma or not, the ability to see information from both an empirical perspective and from the perspective of human stake holders (not empirical), is critical to quality decision making.

Let me give you an example of a non-empirical, intuitive/experiential perspective. If you have ever returned to a playground that you knew when you were young, you may have remembered the sliding board being really high, but now it seems small. It did not shrink. Your perspective changed. This is a fundamental rule of human thought. We learn through experiment (experience). These learnings change the way we view the world. In other words, the context of our information changes.

This is both good and bad. We learn not to put our hand on a hot stove, to look both ways before crossing the street and to not insert keys into electrical wall sockets, because of severe negative consequences. This is the result of the power of observation.

This works well on simple systems where results are not ambiguous, and are easy to understand and predict. On systems where there is complexity and results are not easy to predict, you must “peel the onion” with your observations. When evaluating a complex system, intuition must be used very carefully.

Dr. Daryl Bren does a magic trick with his students on their last day of class with him. The magic trick is really a lesson. He attempts to demonstrate his ability to read a student’s mind by way of giving information about their personal history that he could not otherwise know. He is always successful and his students grapple with what to think about this intriguing skill. Their intuition, based on trust in their professor, compels them to want to believe. Once he has given them enough time, he tells them how he accomplished the feat. Basically he knew who he was going to” read” and collaborated with their family ahead of time, without the student knowing. It is a trick, not magic. He then delivers the punch line, never substitute your intuition for real data.

Another story. Several years ago I had an employee that told me that he had started a rumor about the possibility of a major management shakeup. Two weeks later he came to my office, excited, saying that he had it on good source that there was going to be a major management shakeup. He even had details (facts?), which his intuition bought into.. I had to remind him that he, in fact, started that rumor two weeks earlier and fell victim to it. Intuition, in the absence of fact, will nearly always lead to incorrect conclusions.

This is not to say that intuition is not important. Intuition is a critical evaluation tool, and just like any other tool, must be used properly. Intuition can indicate that either your perspective or the data is skewed in some way. Maybe both are skewed. Intuition will point to what needs a reality check or more information.

This is just another case where balance and perspective play important roles in our lives. In reality, what I am talking about is finding the “why” behind a set of data or “facts”. Successful Six Sigma Projects and quality business decisions depend on it.

Two Dimensional Thinking

If you Aren’t Measuring It You Aren’t Managing It

A favorite axiom in management is, “If you aren’t measuring it, you aren’t managing it”. Just as driving a car with your eyes closed will result in disaster, running a business without some sort of performance feedback will result in business disaster.

The collection and use of data is important because things are rarely what they seem to be. Data helps us separate what is really happening from what we think is happening (or what we want to be happening). When we make decisions based on how things feel or how they have always been, we are operating in the “as we think it is” world. This is a prescription for disaster. The successful business operates in the real world. We call this the “as-is” world.

The measure phase of a Six Sigma process improvement project focuses on characterizing the current performance of a business process, which is the current reality. In this phase, the Six Sigma project team is trying to accomplish two things. First is to establish an “as-is” performance measurement for the process. Second, is to use the data to begin looking for potential causes of defects.

Some of the important activities of the Measure phase are:

- Developing a data collection plan and following it

- Performing a measurement system analysis

- Calculating performance indicators for the process from the data collected

- Control charting

The objective is to measure the process’ impact on the customer’s CTQ (Critical to Quality) issues. The result is the characterization of the process’ performance from the customer’s perspective. This becomes the process’ story in the “as-is” world.

Thanksgiving Notes

This will not be a post about Six Sigma or personal development. It is a time for being thankful and telling those you love how you feel.

Things I am thankful for and people I care about:

My mother and her recovery from cancer surgery.

My wife who deserves recognition for putting up with me.

My grandson Caleb who brings light into every corner of my life.

My son and the difference his life makes with others.

My daughter-in-law whom I love as if she were my own daughter.

My job and the opportunities it gives me.

My friends. Special mention: Lonnie who gave me a job, Brian and Fadi who share my burden at work.

My readers, who follow my words agree or not.

The problem is that when making a list you will undoubtably leave someone or something off by mistake. If I left anyone out, please do not take offense. I am only a human man, flawed, but saved by Grace.

Personal Development and Six Sigma

You might ask why I write about personal development on a website that is supposed to be focused on Six Sigma. This is a question that I hear from those who are trained in Six Sigma, but I rarely hear by those who are not.

The answer is that I see Six Sigma as a paradigm change for business people, not a just statistical business management program. At the end of the day, businesses are operated and managed by people. Any real change in the way things are done will happen at the people level. Failure to understand statistics will not cause a business to fail. Failure to understand the underlying, people focused reasons for why things happen in a business will lead to failure. The “why” is more important than the “what”.

Let me give an example. Business arrogance will cause a business to have a deaf ear toward customers and employees even if the business metrics show a problem. Six Sigma processes and statistics will not solve the problem of a manager who is not a believer or is protecting their turf. Therefore, a paradigm change at the individual manager level has to take place in order to bring business processes in alignment with customer expectations.

The majority of Six Sigma consultants are probably aware of the importance of existing corporate culture and its ability to adapt to the Six Sigma paradigm. At the same time, they probably do not know how to fix the problem and (or) are unwilling to walk away from the job opportunity. The resulting Six Sigma roll out fails because of failure to change the leadership culture. No one is happy as a result.

From a cultural perspective, the change is from the inside out not the outside in. No consultant can push change in an organization. Change is pulled. The impetus of pushed change comes from desire that is outside the organization. The impetus for pulled changes comes from the organization’s internal desire to change. This is where the rubber meets the road in Six Sigma.